Many urban farmers face the problem of not having enough space to grow produce. But growing mushrooms can be done in the corner of a flat — and the “shroom boom” is taking off.

During the Covid lockdowns, many people started reading up on how they could grow mushrooms at home as a cooking ingredient. The documentary Fantastic Fungi on Netflix, the Ted talk by renowned mycologist and fungal activist Paul Stamets and medical research on the psychedelic compound psilocybin in certain types of mushrooms have also greatly stoked public interest.

Mushrooms have nutritional and health benefits, and growing them is environmentally friendly: they grow on straw, logs, sawdust, even coffee grounds.

Home growers feel good about reducing their ecological footprint by reducing food kilometres associated with store-bought produce and packaging.

Growing food at home has psychological benefits; it reduces stress and improves your mood and mindfulness. Raising mushrooms can be a social activity, because people exchange knowledge and experiences related to their cultivation techniques. Many fungi, such as lion’s mane, are used as supplements and can have medicinal benefits if used with a holistic approach.

Mycelium-based materials, or “myco-materials” that fungi create as they grow can be used for multiple purposes, such as making leather or for insulation. Stamets outlines how fungi can be used for recycling oil spills and as environmentally friendly insecticides.

Growing speciality mushrooms is an expanding market that is growing as fast as … well, fungi do. On the commercial side, China, where mushrooms have long been part of the daily diet, is the world’s leading producer. It already churns out around 50 million tonnes of mushrooms and truffles from factory farms annually, and, according to research company Imarc Group, the financial value of the global mushroom market will climb to over $90 billion by 2028 — up from $63 billion in 2022.

Stephen Hobbs

Multimedia artist Stephen Hobbs was living in rural Ireland during the Covid pandemic and became fascinated by fungi during forest walks, when he and his family tried to identify them.

“Having spent much of my professional life working in Johannesburg, the purposefulness of mycelial networks became a powerful metaphysical lens for exploring ideas of social cohesion, especially in the context of the mental health fallout that came with months of lockdown social isolation,” says Hobbs.

“Through The Trinity Session — the artist collective and public art consultancy I’ve co-directed since 2001 — we used our workshop space at The Orchards Project in Orange Grove to explore an art- and nature-centred Green Projects Programme, which, with a variety of partners, implemented a range of interactive workshops that drew on play and art therapy principles in relation to permaculture practices, fungi cultivation and so on.”

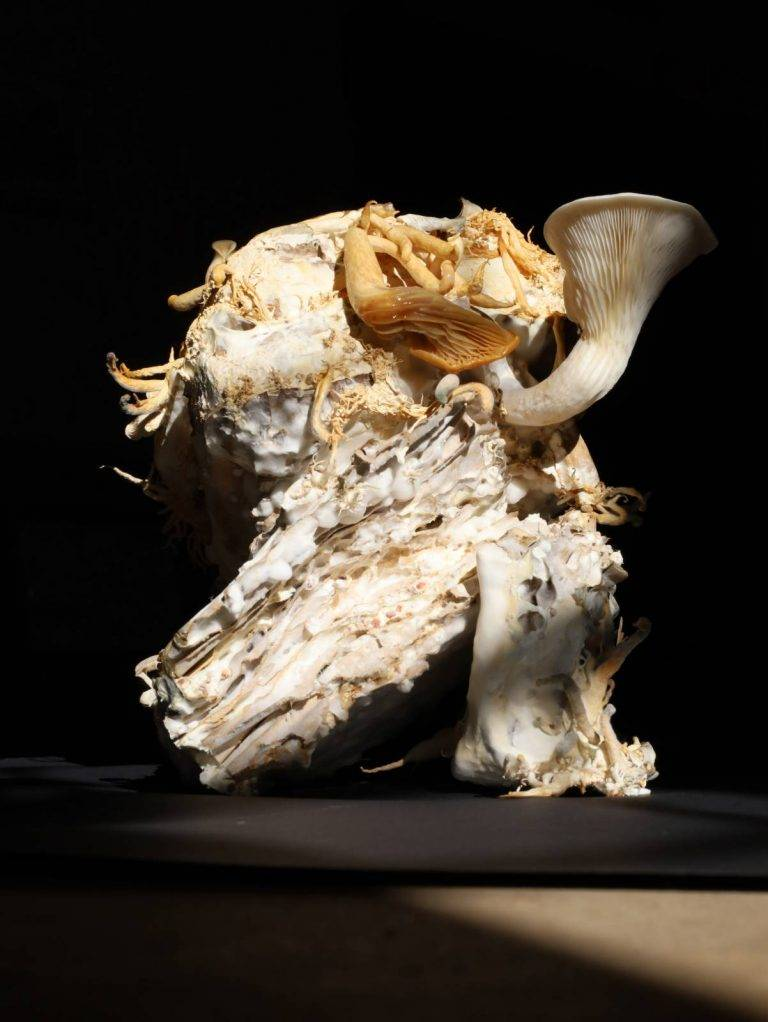

Part of the Green Projects Programme was allowing Afrifungi to set up their mycology lab in the Orchards workshop, and the exposure to their cultivation and growing methods spawned “an entirely new trajectory” in Hobbs’s art. He has incorporated mycelium into a number of his exhibitions, as an attempt to create new commentary on Johannesburg’s intrinsic nature of collapsing and rebuilding.

Afrifungi

The internet abounds with information about how to get your garden going. But there’s also a lot of misinformation out there, which is why Afrifungi has stepped up to “unveil the mystery”.

Through training workshops, the Afrifungi crew of three equip fungi novices and enthusiasts with the knowledge they require to become successful speciality mushroom growers.

They also cultivate spawn — it’s difficult to do this yourself — and tailor-make solutions for them. A big part of their initial challenge was deciding which part of the fungi growing process to hone in on, because the field is so vast.

“The focus is on oysters and shiitake mushrooms, because they are the easiest to grow. Oysters grow on a wide variety of substrates; shiitake grow on logs, and they are definitely the tastiest. There’s a wide variety of oysters, of many colours, which you can grow for years and never get bored,” says Melinda Dunnett.

Matthew Keulemans explains the typical process a trainee follows: “You start with a workshop on growing fast-yielding oyster mushrooms, kindled by curiosity; then you learn how to pasteurise straw by boiling it, or soaking it in a hydrated lime solution; the straw is packed into a prepared bucket, then you add grain that is colonised, called spawn; then you do a ‘lasagne’ process, of adding straw, then spawn, etcetera. You have already prepared a bucket with holes that are taped. Then you put it in a darkish space with stable, ambient temperature and humidity; then you spray the outside of the bucket to maintain humidity.

“After that, you keep watching, and once the mushrooms start pinning [fruiting], they grow continuously for a period of time. Or you can take a shiitake log home and grow it in your garden, in a microclimate that suits it.”

Is growing mushrooms easy? Yes and no. Mushrooms may not need much light, but they do require a stable environment. Hobbs says he finds it “easier to grow shrooms than spinach”, but adds that paying close attention to the mushrooms as they pin is more important than knowing the theory; it’s a state of mind, an “exchange of magic” that requires really focused intention.

“You can even call it a ‘return of faith’ — you have to surrender your logic,” says Sven Mollgaard. “There’s so much excitement when you get your first pinning; many students come because of the novelty factor, but lose faith because they’re not getting consistent results.”

The Urban Ruins

Clayton Viljoen, chief executive of The Urban Ruins, an early childhood development centre in Boksburg that feeds up to 600 children each week in the area from a food garden, says they invested in growing mushrooms to help their nonprofit generate an income.

In 2023 a funder gave them some money and after doing research, they decided to invest in growing oyster mushrooms. The staff trained with Afrifungi and set up six insulated and temperature-controlled wooden huts. One is a “dark room” for seeding and the rest are used for fruiting.

The process is quite technical, he says, and hygiene is paramount. “The growing process itself is simple but easily corrupted. We use lime-cleaned buckets filled with straw, as Afrifungi taught us, for growing the spawn.”

Growing mushrooms was chosen because of space constraints; other forms of income the organisation have are a call centre and a programme that collects and sells second-hand household items. The mushrooms are sold to shops in Boksburg such as Food Lovers Market, and this is generating “quite a substantial” revenue, according to Viljoen.

Mushrooms and urban farming

Mollgaard says: “We think growing mushrooms should be part of any urban farming project, on any scale. It gives us valuable insight into living systems, into how we maintain healthy soil, and what the connections are between fungi and microbes. It’s also a healthy and nutritious crop, and is high value, so it’s a really good income stream.”

Dunnett says mushrooms can be integrated with and grown underneath other crops; the vegetables can create the shady micro-climate needed for some types of fungi that grow in soil. The mushrooms help to create healthy soil for other crops, and vegetable substrates that are often regarded as waste, such as mealie cobs, can be used for growing fungi, so growing fungi can close loops in the urban farming process.

“Once the value of a substrate has been ‘used up’ for growing mushrooms, it can then be composted, or used for mulching, so it gets returned to the soil, and there is no agricultural waste. All your resources get used, and if you don’t have the right substrates, you can, say, swap them with a neighbouring farm,” she says.

The mycological network

In Europe a huge variety of mushrooms grow in the wild; one might even find a delicious King oyster growing on a log in the forest. People keep finding mushrooms and want to know what species they are, and many share their growing tips. The cross-pollination between amateurs and experts is vital for expanding knowledge about fungi; there are millions of species, and only about 150 000 are known to date.

Locally, the Mycological Societies of Southern Africa have this kind of network going, and Afrifungi, which is a member, is becoming part of a network of small-scale growers in the country. The crew often visits the Western Cape to conduct workshops.

“There’s more openness to the permaculture culture and mindset in the Cape; there’s more space and more people growing their own food down there than in Joburg, but interest is growing nationwide,” says Keulemans.

Joburg is quite dry during the winter, so ensuring the conditions remain stable and humidity is maintained is necessary based on the season, microclimate and prevailing weather conditions: “Just in this yard, you may find 10 different microclimates.”

He adds: “There were a lot of small-scale farmers who were growing in containers, who really suffered when load-shedding came along; you can’t grow indoors without backup energy systems. We try to encourage low-tech, outdoor fungi farming — growing on logs, or in oyster mushroom towers in your own backyard — which can be done alongside growing your own veggies.”

Exactly what are fungi?

Fungi, the nutrient cycling agents of the natural world, can be single-celled or complex multicellular organisms. They resemble humans more than plants and can be found in just about any habitat, but most live on land. A group called the decomposers grow in the soil or on dead plant matter, where they play an important role in decomposition and cycling carbon and other elements.

Neither plants nor animals, fungi digest their food by externally secreting enzymes. The three main groups of fungi are the multicellular filamentous moulds; the macroscopic filamentous fungi that form large fruiting bodies, commonly referred to as “mushrooms”; and single-celled microscopic yeasts, such as those used for making bread and for brewing.

Plants provide fungi with access to food, while fungi provide plants with access to water and nutrients — a relationship that many scientists believe allowed the initial colonisation of land by plants. Mycelial networks beneath the ground also allow plants to communicate with each other, and even share nutrients.

Hobbs says: “There’s always this concern with two things, which comes up in the Afrifungi workshops: magic mushrooms and poisonous mushrooms. We have to demystify this constantly. There’s only a limited number of psychedelic and dangerous mushrooms.”

The only recorded instance of hallucinogenic mushrooms being used traditionally in Africa was recently documented: Psilocybe maluti is apparently used by Basotho healers in Lesotho.