William M. Ciesla is Forest Protection Officer, FAO Forest Resources Development Branch.

The gentle rolling hills of central Kenya present an attractive landscape. This is a region of small farms and pastures interspersed with patches of native forest, woodlots and wind-breaks. Typically, the woodlots and wind-breaks are plantations of Mexican cypress, Cupressus lusitanica Mill., a straight, fast-growing tree which is native to Mexico and the high mountains of Guatemala. Farmhouses are often surrounded by dense, neatly trimmed hedges of this same species.

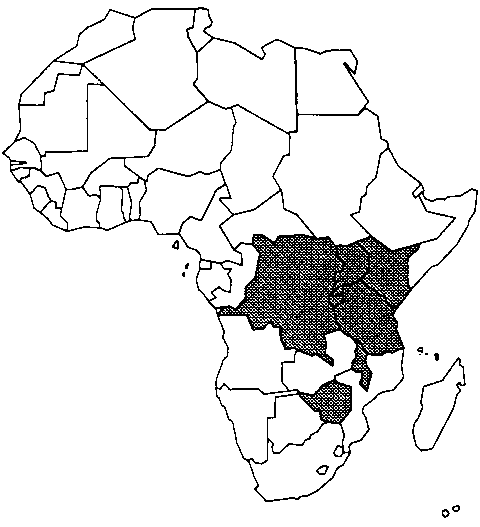

Today, this landscape is undergoing a dramatic change. The cypress trees, once lush and healthy, are turning a sickly red colour. A similar discoloration is seen in woodlots, wind-breaks and hedges in the neighbouring United Republic of Tanzania and Uganda, the eastern portions of Zaire, Malawi and other countries of eastern and southern Africa. The cause of this discoloration is the cypress aphid.

The insect

Cypress aphid, Cinara cupressi (Buckton), is one of the giant conifer aphids, a group of about 175 species that infest twigs and branches of many conifers in the Northern Hemisphere. Occasionally they become abundant enough to cause damage in their native habitat but, as a rule, they are not considered major forest pests.

The life cycle of the cypress aphid is complex. During the summer months, only females are present and reproduce parthenogenetically (without mating), giving birth to live young. There are two forms of adults: a winged and a wingless form. As cool weather approaches, both males and females are found and eggs are produced instead of live nymphs. The eggs are laid in rough areas on twigs and foliage where they overwinter. Several generations are produced in a year and the life span of a single generation is about 25 days during the peak of the growing season. Adults and immature insects are found in clusters of as many as 80 individuals on the branches of host trees where they suck the plant juices from the stem. In order for the cypress aphid to digest these juices, a salivary fluid must first be injected into the stem. These fluids are toxic to some trees and can cause branch dieback and eventually tree mortality, especially when large numbers of aphids are present.

A colony of cypress aphids on the stem of Cupressus lusitanica

Cypress aphids also produce copious amounts of honeydew, a sweet, sticky material that covers the branches and foliage. This material provides a medium for the growth of sooty mould, a black-coloured fungus which covers the foliage and which can interfere with photosynthesis.

Distribution and hosts

The cypress aphid is widely distributed in Europe, the Near East, the Himalayas and North America. Its hosts are members of the conifer family, Cupressaceae, including Juniperus, Cupressus, Thuja, Chamaecyparis and Widdringtonia.

In Europe and the Near East, the cypress aphid infests a wide range of introduced trees, among which are Cupressus arizonica Greene, C. macrocarpa Hartweg, C. sempervirens L., and Thuja occidentalis L. Several native species of Juniperus are also attacked. Damage has been reported in Italy, Israel and Jordan and the insect has also been collected in northern India on Juniperus recurvara Buchanan-Hamilton.

The cypress aphid is widely distributed in North America where it has been known under two other scientific names: C. canadensis Hottes and Bradley and C. sabinae (Gillette and Palmer). It has been reported in Pennsylvania and Colorado, the United States and in British Columbia, Canada where its hosts are Juniperus virginiana L. and J. scopulorum (Sargent) Jones. There have been no reports of damage.

Current situation in Africa

C. cupressi is the fourth species of conifer-infesting aphid to have been introduced into Africa. The others all infest pines and include the closely related Cupressus cronartii Tissot & Pepper, the pine woolly aphid, Pineus pini (Macquart) and the pine needle aphid, Eulachnus rileyi Williams. The introduction of C. cupressi has thus far had the most severe economic and social impacts.

The first discovery of C. cupressi in Africa was in Malawi in 1986. During the following year, the insect was discovered in the United Republic of Tanzania. Infestations have subsequently been reported from Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Zaire and Zimbabwe.

In Kenya, the first infestation was discovered in March 1990. Three months later, surveys conducted by the Department of Forestry showed that the insect was present in over 80 percent of Kenya’s forests. In addition to Cupressus lusitanica, trees which are attacked by the cypress aphid in Africa include several other introduced species of Cupressus and Callitris. The indigenous Widdringtonia nodiflora, Malawi’s national tree, and Juniperus procera Hochstetter, a common tree of high elevation forests in parts of Kenya and the United Republic of Tanzania, are also attacked.

Damage and impacts

In the warm climate of eastern and southern Africa, the cypress aphid does not overwinter for a prolonged period in an egg stage. Parthenogenetic reproduction continues the year round and this, coupled with the absence of natural enemies, has allowed cypress aphid populations to increase rapidly.

Feeding causes desiccation of the stems and the progressive dieback of heavily infested trees. Dieback usually occurs from the inner crown outward and from the lower crown upward. Unless infestations are treated promptly, death of trees which are sensitive to the feeding of the cypress aphid is imminent.

Cupressus lusitanica is extremely sensitive to feeding by the cypress aphid. This tree is a highly favoured plantation species because of its rapid growth rate and excellent form. It matures in about 25 years and plantations on good sites are capable of producing an average of 300 m³ per hectare at final harvest. In Kenya, this species is planted on about 86 000 ha and comprises approximately 45 percent of this country’s total industrial forest plantation area.

Loss of these plantations could have serious effects on Kenya’s domestic wood supply. Furthermore, Cupressus lusitanica is a key agroforestry species in eastern and southern Kenya and is widely planted for wind-breaks, as a source of fuelwood and as living fences and hedges.

In addition to being a direct loss of forest resources, the presence of a substantial number of dead trees provides a large volume of fuel which can increase the destructive potential of wildfire. Many homes in rural areas are surrounded by dry, dying cypress hedges, the presence of which poses an imminent fire hazard and could result in loss of life and property.

Juniperus procera is an important indigenous species in high elevation forests in portions of eastern Africa. In Kenya alone, there are 280 000 ha of this species in plantations and natural forests. It too is damaged by the cypress aphid but, to date, damage has not been as severe as that occurring on Mexican cypress. Losses of this tree in water catchment areas could result in soil erosion and a deterioration in water quality.

A plantation of Cupressus lusitanica.

This straight, fast growing tree is a favourite plantation species in eastern and southern Africa and is highly sensitive to the feeding of the cypress aphid

Pest management options

Chemical control. Ground applications of chemical insecticides have been used against the cypress aphid by several East African countries but, despite successful reduction of aphid populations, some trees and hedges have continued to die. Timing is 8 critical factor in the use of insecticides. Infestations left untreated for more than 20 days tend to have a permanent effect on host plants. In addition, the use of chemicals poses an environmental hazard as well as jeopardizing applicators and local residents. These materials are best used sparingly and as a last resort in high-value forest areas.

Silvicultural management. The cypress aphid appears to be a shade-loving insect.

Colonies are usually found in the inner crown amid dense foliage. The thinning of plantations could possibly create conditions less favourable for population buildup. The establishment of plantations on sites where soils are shallow or where there is insufficient moisture may place host trees under stress and make them more sensitive to attack.

There is a highly variable pattern of damage among individual Mexican cypress trees in plantations. Some trees discolour rapidly once infestations are established while others seem to be more tolerant. This indicates that there may be some genetically based variation in resistance to feeding damage. Propagation and planting of resistant genotypes could be a means of managing this insect in the future but requires further investigation.

Another possibility is the use of species which are less sensitive to cypress aphid attacks. For example, Cupressus torulusa Don., a species native to the Himalayas, appears to be more tolerant to attack when planted in Africa. However, these approaches require testing and evaluation before they can be recommended for application on a wide scale.

Biological control. Introduction of natural enemies – parasites and predators – is a technique that has been used with a high degree of success against a number of exotic pests in both forestry and agriculture. This approach was used successfully against the closely related Cinara cronartii, a pine-infesting species native to the southeastern United States and which was discovered in South Africa in 1974. A parasitoid, Pauesia sp. was discovered, collected and released in South Africa. Following the successful establishment of the parasite, aphid populations collapsed.

Although it is known that natural enemies of the cypress aphid exist in this insect’s native habitat, little is known of their life history, habits or adaptability to different climatic conditions. Special surveys must be conducted to identify promising candidate species for possible release in Africa.

Integrated pest management. Effective management of cypress aphid in East Africa, as is the case with any other destructive pest, is best conducted within the context of integrated pest management (IPM). IPM consists of several ecologically sound biological, cultural; genetic and mechanical tactics used alone or in combination to reduce pest populations to tolerable levels. The use of chemicals can be part of an. IPM programme but they are generally used sparingly and as a last resort.

Need for emergency action

Long-term management of this insect will undoubtedly rely on a combination of silvicultural, genetic and biological tactics. These must be developed and tested through a comprehensive programme of research and development. In the interim, several short-term tactics can be applied which will afford protection to the forest resource. These include:

– Accelerated harvesting of mature or nearly mature cypress plantations which are in danger of dying in order to recover values, reduce fire hazards and eliminate possible breeding places for borers and other pests.

– Removal of dead and dying hedges from around home sites to reduce fire hazards.

– Judicious use of chemical insecticides to protect high-value stands around rural home sites.

What is being done

In response to a request from the Government of Malawi, FAO has sent a consultant to evaluate the status of aphids, including the cypress aphid, in the country’s coniferous plantations and natural forests. A special project involving both research and operational activities has been developed. In addition, the International Institute of Biological Control (IIBC), an organization based in the United Kingdom, has begun a search for natural enemies of the cypress aphid and two other species of pine-infesting aphids for possible introduction into Malawi.

In Kenya, FAO has funded an emergency Technical Cooperation Programme project to help initiate emergency control measures and to serve as a bridge until a longer-term project gets under way. The full-scale project will address operation control, research and development and technology transfer with the ultimate goal of establishing an IPM system within five years. FAO specialists have provided technical assistance to the Kenya Forest Research Institute (KEFRI), the Department of Forestry and the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) for the development of a master plan.

FAO also collaborated with the IIBC and the United States Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service in a recent workshop on conifer aphids in Africa, organized by KEFRI. One of the primary objectives of this workshop was to strengthen networking among scientists and foresters in the countries affected by conifer aphids.

Once long-range pest management options are developed and are ready for operational use, provision must be made for their application. The transfer of research information to operational use is best accomplished through the development of a strong subregional network of research scientists and pest management specialists working toward a common goal: the effective management of this new threat to the forest resources of East Africa.

Bibliography

Agarwala, B.K. & Raychaudhuri, D. 1982. Two species of Cinara Curtis, from India with a description of a new species (Homoptera: Aphididae, Lachnidae). Akitu Journal, 46.

Binazzi, A. 1978. Contributi alla conoscenza degli afidi delle conifere. 1. Le specie dei Genn. Cinara Curt., Schizolachnus Mordr., Cedrobium Remaud ed Eulachnus D. Gu. presenti in Italia (Homoptera: Aphidoidea: Lachnidae). Redia LXI: 291-400.

Browne, F.G. 1948. Pests and diseases of forest plantation trees. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Drooz, A.T. ed. 1985. Insects of eastern forests. Misc. Pub., 1426. Washington, D.C., USDA Forest Service.

Eaton, V. F. 1972. A taxonomic review of the species of Cinara Curtis occurring in Britain (Homoptera, Aphididae). Bull. British Museum (Natural History), Entomol., 27: 103-186.

Furniss, R.L. & Carolin, V.M. 1977. Western forest insects. Misc. Pub., 1339. Washington, D.C., USDA Forest Service.

Inserra, R.N., Luisi N.& Vovlas, N. 1979. Il ruolo delle infestazioni dell’afide Cinara cupressi (Buckton) nei deperimenti di cipresso. Informatore Fitipatologico, 29: 7-11.

Kabungo, D.A. (n.d.) A preliminary report on cypress aphid in the southern highlands of Tanzania. 1987-88. SKU/1/9/18, Vol II. Mbeya, Tanzania, The Uyole Agricultural Centre.

Kessy, B.S. 1990. Major pest problems: Tanzania. In Proceedings, IUFRO, 2: 259-269. Montreal, IUFRO.

Kfir, R., Kirsten, F. & Van Rensburg, N.J. 1985. Pauesia sp. (Hymenoptera: Aphididae), a parasite introduced into South Africa for biological control of the black pine aphid, Cinara cronartii (Homoptera: Aphididae). Environ. Entomol., 14(5).

Mendel, Z. & Golan, Y. 1983. The cypress aphid (Cinara cupressi), a new pest of cypress in Israel. Hassadeh J., 63(12).

Mills, N.J. 1990. Biological control of forest aphid pests in Africa. Bull. Entomol. Res., 80: 31-36.

Mnzava, E.M. 1980. Village afforestation: lessons of experience in Tanzania. TF-INT-271 (SWE). Rome, FAO.

Notario, A. & Barango, J. 1990. Los pulgones de las coníferas de España. Proceedings, IUFRO, 2: 226-231. Montreal, IUFRO.

Odera, J. A. 1991. Some opportunities for managing aphids of softwood plantations in Malawi. Assistance to Forestry Sector, Malawi, MLW/86/020. Rome, FAO.

Speight, M.R. & Wainhouse, D. 1989. Ecology and management of forest insects. Oxford, Clarendon Press.