Recent reports indicating that veterinarians are leaving the country en masse have caused a stir. The parliamentary portfolio committee for agriculture reported that about 100 of the 160 veterinarians who graduate annually from Onderstepoort emigrate, but experts dispute this figure.

While the shortage of veterinarians over the years is not denied, Dr Paul van der Merwe, chairperson of the South African Veterinary Association (Sava), says it is difficult to provide accurate figures. He estimates that between 120 and 160 students graduate each year, but this number varies.

He says veterinarians who wish to emigrate require a certificate of good standing from the veterinary council, and last year 170 certificates were issued.

“What concerns us is that more certificates were issued in one year than people who graduated,” says Van der Merwe.

“I’ve been the president of the association for three years and the situation is only getting worse, especially in rural areas. We see the shortages and receive notices of more practices closing. The latest was in Beaufort West, and if you can’t even keep a practice running in a town of that size, then it becomes a crisis.”

Van der Merwe says he knows of a veterinarian in Plettenberg Bay who has struggled for three years to find a partner.

“You would think everyone would jump at the chance to work in Plettenberg Bay, but he can’t find suitable candidates who are willing to, for example, travel long distances for their work.”

RURAL CHALLENGES

Van der Merwe says Sava has identified three main causes for this problem in rural areas.

“The first major problem is compensation. The veterinarian in the city quickly treats a puppy in 15 minutes and has completed a service. Then there’s the rural veterinarian who leaves at 4am to travel 300 km to a farm to attend to a sick animal then drives all the way back. How does he bill the farmer for that day’s work?”

He says a student with a study loan graduates from Onderstepoort with debt of R2 million-R3 million which must be repaid monthly at R15 000-R20 000. If the student earns R30 000 after deductions, there’s not enough left to live on. A student who goes to work in the UK can earn three times as much as in South Africa and pay off their student debt within five years.

The second problem is collegial interaction. “For many students, their compulsory community service year turns into a nightmare. A woman can end up in the middle of the Transkei in a clinic that’s a wooden hut without any equipment, and then she’s expected to do the work without any assistance from the provincial government.”

He says his daughter only saw her supervisor on the first day of her community service year and never heard from him again or received any help.

One of the shocking statistics is that when asked about emigration, 80% of the 2022 cohort said they were considering it, he said.

The third problem is clients’ expectations. “Five years ago, there was a practice with five veterinarians. Now, only the owner of the practice remains but the clients expect the same service,” says Van der Merwe.

“I know of an 80-year-old veterinarian who has to work from early morning until late at night. It’s a vicious circle. The more pressure there is, the more veterinarians leave and the greater the pressure on those who stay behind. Safety is also an issue, but not the most important one.”

Van der Merwe says Sava wants to help young veterinarians with mentorships and guidelines to ensure they aren’t exploited, but funds are limited. The organisation depends on membership fees but loses about 15 members a month. Other funding sources are being sought.

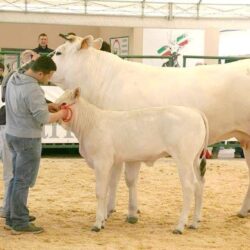

Photo: Onderstepoort/University of Pretoria

DATA UNCLEAR

Prof Dietmar Holm, a veterinarian and cattle specialist at the University of Pretoria, says there is no accurate information on how many veterinarians leave the country. The certificates issued by the council do not necessarily mean these vets will leave. He believes the community service year is a good development, and once a student completes it the chances are good that they will stay in the country.

“People are too negative. The reason why people leave the country is not a veterinary problem but a South African problem. Professionals leave the country for financial and political security. They want to work where there is money.”

He says the situation should also be viewed in the long term. When he graduated in 1998, it was the end of the Mandela era, and due to significant political uncertainty he and almost all his fellow students left the country. Most, however, returned after a few years.

Dr Danie Odendaal, director of the Veterinarian Network, says 60% of his class also worked abroad for a time and all returned. He believes this is normal. There are, however, older veterinarians who emigrate due to uncertainties and for safety reasons.

He believes that if there is a shortage of veterinarians in a certain part of the country, then it is not economically justifiable to be there. “If it can be economically justified, there will be a veterinarian. There isn’t really a shortage.”

He says technology also plays a larger role in providing services. For example, preventive services can be delivered to 200 farmers through mobile phone technology, which was not previously possible.